Did You Ever Wonder How a Chinese Dictionary Works?

August 13, 2019

Did You Ever Wonder How a Chinese Dictionary Works?

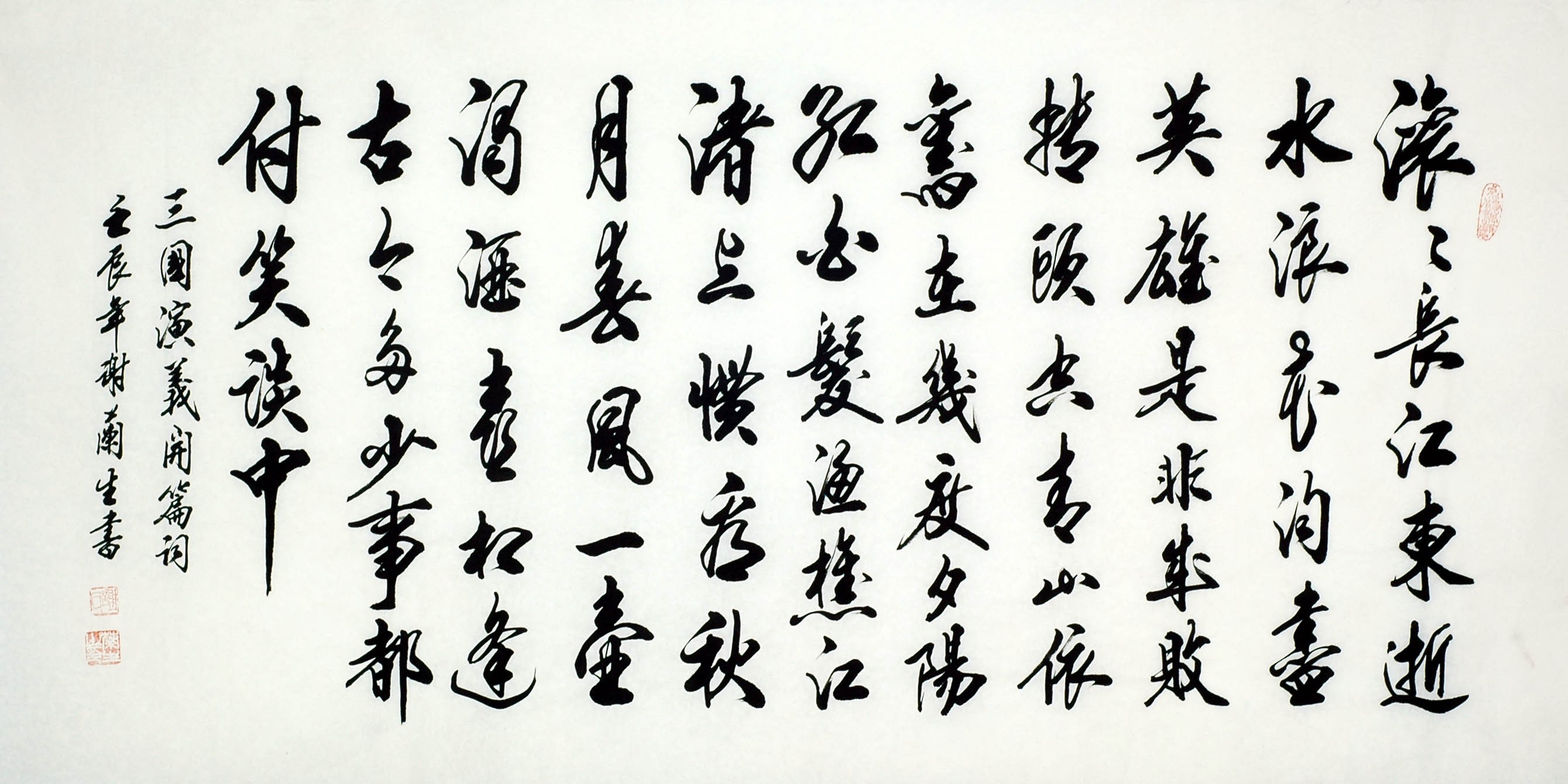

Think of any dictionary you’ve used—English, Spanish, French. They’re all organized alphabetically, right? But here’s the puzzle: Chinese doesn’t have an alphabet. Sure, you might see pinyin (the Romanized spelling like “ni hao”), but that’s mostly for learners or for inputting Chinese on computers. It’s not the traditional way—and certainly not how older generations in China learned to read and write.

So . . . no spelling? Imagine never second-guessing whether you used “there,” “they’re,” or “their.” Or skipping that moment of panic over a silent “gh” or “I before E.” That headache doesn’t exist in Chinese. But if you have thousands upon thousands of characters, how do you organize a dictionary?

That is where radicals and stroke counts come in. Traditional Chinese dictionaries often group characters by their “radical” (a key part of the character that hints at meaning or category, like “water” or “hand”). Then, within those radicals, characters are further sorted by the number of strokes it takes to write them. It’s like having a giant matrix where each row is a radical, and each column is a stroke count.

The process might be slower for someone used to quick alphabetical lookups, but it’s surprisingly logical once you get the hang of it. Over time, publishers and educators have developed other methods, such as sorting by pinyin (sound), or even electronically by just writing the character on a phone screen. But at the heart of it, the radical-plus-stroke method remains a classic, especially for people wanting to see how the character is built and how it connects to its etymology.

So yes, no alphabet, no spelling. But an entire system that’s just as structured—maybe even more so—than the A-B-C approach. Next time you see a Chinese dictionary, you’ll know there’s a whole different logic behind how those pages are arranged. Kind of makes you appreciate how flexible language, and the art of cataloging it, can be.